Thesis Writing: The Basics

/Note: This is a long post, but so is the thesis writing process. But stick with me. We'll get through this together, I promise.

I have written three theses in the past four years. I completed my undergraduate thesis in spring 2010, then my first Master’s in 2012, and then turned in my second Master’s thesis in the summer of 2013. By the time I was starting that third thesis journey, my strong sense was “oh no, not again.” But here’s the thing: a thesis is a student’s chance to pursue one specific research area to the absolute extent of what they’re able to accomplish. Particularly for undergraduates, a thesis might be the first time you actually get to choose the focus, methods, and scope of a research project. You are in control.

This is incredibly empowering.

It is also profoundly terrifying.

The first fully-printed draft of my undergraduate thesis.

Almost anyone would be intimidated by the prospect of a large and completely self-driven research project. We’re not really prepared for it by our coursework—having to write a ten-page final essay for a semester-long class is one thing. A thesis is quite another.

Despite the intensity and scope of the process, if you are one of those students that gets to choose whether or not to undertake a capstone or honors thesis to round out your undergraduate career, I highly recommend at least exploring the idea with an academic adviser or a professor you particularly enjoy working with. If you plan to continue your education, a thesis is invaluable for use as a writing sample and will be included permanently on your academic CV. It is also a chance to prove that you really, really learned and can speak to one specific thing from your undergraduate study.

Of course, each person’s thesis experience is unique to them, and also depends on their area of focus and the style of their research. A lab-based chemistry thesis project will look vastly different than a thesis based on the translation of a body of foreign-language poetry. While the details, methodology, and timeline are unique to the individual, however, there are some broad steps that have to happen in the process, and that’s what I am outlining here.

Before I do, let me just say first that the most important thing you can possibly do for your thesis process is to be confident. Be bold, be self-directed, and take ownership of your project and the opportunity. Ask for help, build a support system of others doing their thesis at the same time, and believe that you will get it done. Nothing matters more than confidence. Get out there and get it done!

So here are the basics. The boiled-down essentials for crafting and writing your undergraduate thesis.

Step 1 Identify a topic

This sounds obvious. But it can be an emotionally fraught and complicated process to narrow your focus to one particular and feasible topic. In the early stages (and these early stages should probably be more than a year from when your thesis is due), the topic can be somewhat broad. It can be “20th Century American feminist literature.” Or “invasive plant species in the nearby woodlands” or “political graffiti and street art.” I called these topics “somewhat broad,” and while you might think these are specific, hang in there because we’ve got way more focusing to do.

At this stage

Focus down from your major to one specific aspect of it.

Imagine what you would like to spend the next year of your life studying.

Think of what truly interests and inspires you.

Imagine telling a group of professors in your department about your topic. Is it a good fit?

Do not

Worry about what your parents/cousins/neighbors will think. This is an academic thesis, and not for public comment.

Panic over the methodology or research portion. You are picking a topic. Methods come next, and with support from your advisers.

At this early stage, it might be a good idea to think about a “front runner” thesis topic, and to also develop a backup that you like almost as well. Again, the point is not to panic about feasibility at this stage. It’s to begin to develop your options.

Step 2 Background research

Figure out who is talking about your topic in your field. Use your library search to identify the recent books and journal articles examining and discussing your topic. There will probably be a lot, and that’s a good thing: that means you fit within the academic discourse within your discipline. Get a few of the most recent and most interesting-looking articles and books, and do a read them. Take notes. Look at their bibliographies. Get a feel for how popular this topic is, and the scope of attention being paid to it.

Your goal while doing this research is to understand where your research fits, and to begin to get a sense of where you might add your unique voice and perspective to the conversation. Are there any gaps in the scholarship? Can you think of a new or different area or methodology to bring to bear on the topic?

Don’t panic at this stage, and don’t read everything you could ever possibly find. Narrowing your topic and making a detailed research plan comes later. For now, just figure out your context, and start to get a perspective on who’s doing what, and how. Take notes, since this could be the start of your bibliography. Pay attention to how you feel about what you’re researching: do you finish an article and feel more excited and intrigued? Then you’re probably on the right track.

At this stage

Develop your background knowledge.

Start to recognize the big names and key thinkers in this area.

Understand the dominant theories and arguments on the topic.

Build a bibliography of where to start.

Do not

Get overwhelmed by the enormity of the task before you.

Feel that everything has been done already. It hasn’t. I can almost guarantee it.

While your in this stage it’s not a bad idea to also head on over to that source of eternal academic mixed feelings: Wikipedia. I recommend this NOT as a source of academic thought, but just to ensure that you really do know the basics of your topic, and the subject’s history and connections. This is not a source to cite in your thesis. It is, however, a useful tool to make sure you actually know what you’re getting into.

Step 3 Approach advisers

The exact nature of the adviser/student relationship depends on the university, department, and quirks of individual personality. However, it is essential to identify who can help you with your chosen topic, and to establish that advising relationship. This is a topic I will cover in more depth in the future, but the essential elements of this step are:

Someone with expertise on your subject

Someone you can work with

Someone willing to work with you

Someone with experience mentoring undergraduates in their thesis process

Someone to help you identify the various stages of research, outlining, drafting, editing, and (possibly) undertaking an oral defense or presentation of your research

This “someone” might, in fact, be multiple people depending on your department and needs. It might be that someone on staff in the office is designated a thesis adviser, or can be persuaded to help walk you through the process. I strongly advise you to take advantage of all resources available to you.

When approaching a potential adviser, let them know ahead of time that you have read the thesis guidelines for your department, that you have identified a couple of potential topics, and that you have begun background research. You do not have to pretend to know everything from the get-go. But you want to signal that you are prepared and willing to do the work.

At this stage

Identify multiple potential advisers based on their expertise and personalities.

Approach potential advisers with clear and focused thesis proposals.

If a professor agrees to advise you, clarify how often you should meet, what they expect to see in the forms of drafts and outlines, and what you can expect from them.

Clarify that they approve of your topic, and begin to narrow the focus for the subject of your thesis based on their advice and your research.

Do not

Delay this step. You need an adviser, and this relationship is key to the success of your thesis.

Pick an adviser on an arbitrary or casual manner.

Set your hopes on a specific single person. There should be multiple faculty members suited to your general area of interest. Approach several. Do your research on their areas of interest.

Show up unprepared.

Panic.

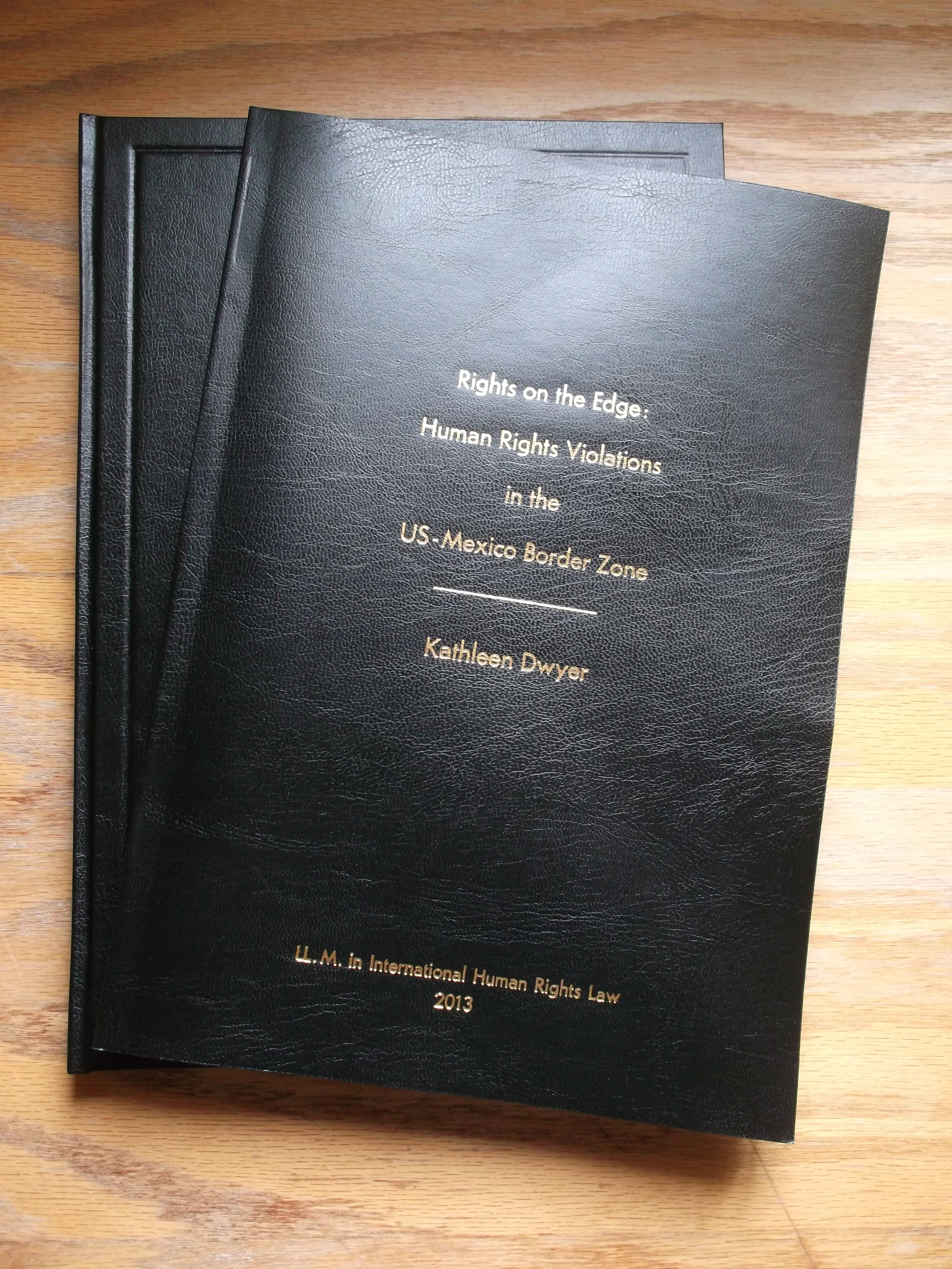

The printed and bound version of my Master's thesis in Human Rights Law at the National University of Ireland in Galway.

Step 4 Develop your specific topic

This is where my general advice will become less helpful. Your adviser and specific area of study will have a huge influence on the degree of specificity and the nature of research you conduct for your thesis.

However, regardless of your area, you need to narrow your focus. Take your general topic and focus down to a manageable, researchable subject. Something you can turn into an argument that you can support with research. Thus, “20th Century American feminist literature” could become “The development of strong female characters in popular 20th Century American feminist literature examining works by ______, _______, and _______.” Or “The false promise of feminism in 20th Century American feminist literature, how _____, ______, and _____ fail to live up to their ideological goals. The topic “invasive plant species in the nearby woodlands” might become “Mapping the spread of English ivy in the ______ woodlands and measurement of associated decline in biodiversity” or “measuring impact of invasive species reduction in _____ County, and proposals for more efficient solutions.” “Political graffiti and street art” could become “Political graffiti in _____ City during the 2012 Presidential election cycle” or “Evolution of the use of ____symbol in contemporary political graffiti and street art in ____ City.”

These are just examples. None are my area of focus, and I don’t know that any of these specific topics would make it past an adviser meeting. But this is how you focus and narrow your topic. It’s the time when methodology and research start to come into play. How will you conduct studies? On what basis will you make your claims? Will you analyze a set of documents, perform surveys, conduct interviews, take on supervised laboratory experiments? All of this will impact your specific topic and how you will narrow your thesis subject.

At this stage

Continue to research the background of your subject area.

Read related theses and pay attention to scope and methodology.

Meet with your adviser to discuss feasibility and focus.

Make arrangements to conduct the necessary research.

Focus, focus, focus!

Don’t

Be too ambitious about what you can take on for research. This is an undergraduate thesis, and you will be limited by time and reach as far as who you can access and what you can reasonably accomplish. However…

Don’t sell yourself short. You can absolutely come up with an interesting and worthwhile topic, and find a unique angle for research and analysis.

Pin all your hopes on a single topic. Talk with your adviser and figure out what will work.

Step 5 Research

Do the research. Ask for help, take advice. Be thorough, take good notes, and get it done.

At this stage

Be organized.

Be bold.

Be proactive.

Be prepared for unexpected results.

Step 6 Outline/create a prospectus/abstract

Develop your argument, and identify your sub-chapters and key points to hit. Be able to summarize your topic, methodology, and findings in a single paragraph. Get the clarity and organization side down early. (See my post on the Five Paragraph Essay for some basic structure advice)

Each chapter of your thesis should read like its own shorter essay.

At this stage

Know what you need to cover in your thesis.

Know your argument.

Know the surrounding literature on your topic.

Know what information fits where in your thesis.

Do not

Get discouraged.

Try to write your thesis without an outline.

Step 7 Drafting

Now you’ve got to write. And you have to go forward boldly and just get the thing written. The first draft does not need to be perfect. It just has to be done, and done well enough to improve upon and develop into what you’ll eventually turn in as your thesis. Set yourself goals for each writing session, drink lots of caffeine, call on your friends and community to support you, use a study buddy, and just get the thing written. This is the hardest stage in a lot of ways. Just believe you can get through it. Get it done.

At this stage

You should start to see the shape of the final thesis.

Identify any areas you need to go back and expand through secondary research or additional analysis.

Check sections off your outline.

Write until it’s done.

Don’t

Show people early drafts unless you feel really confident. They’re not representative of the final product, and could easily discourage you.

Edit extensively as you go. This might just be my personality, but I get exhausted by editing and can get bogged down in the details. You need a first draft. The editing comes later. Get the words on the page, and then you can edit.

Procrastinate. Set up writing goals and people to keep you accountable. Leave yourself enough time for edits and future drafts.

Panic. Don’t panic, it’ll get done.

Step 8 Rewrites

Edit your first draft and send sections to your adviser(s) for feedback. Get peers to help you edit. Fix holes in your argument. Polish. Work through the whole thesis multiple times, making the necessary changes as you go.

At this stage

Ask for help.

Focus on details.

Implement adviser feedback.

Answering questions at the oral defense of my first Master's degree in Conflict and Dispute Resolution.

Step 9 Finalize

Maybe you have to do an oral defense. Maybe there are formatting details for submission. Maybe there is a formal feedback process you need to go through for your school to recognize your thesis. Whatever details you need to take care of, make sure you take care of them. Make it happen, and stay on top of the process. Get it done.

Step 10 Done

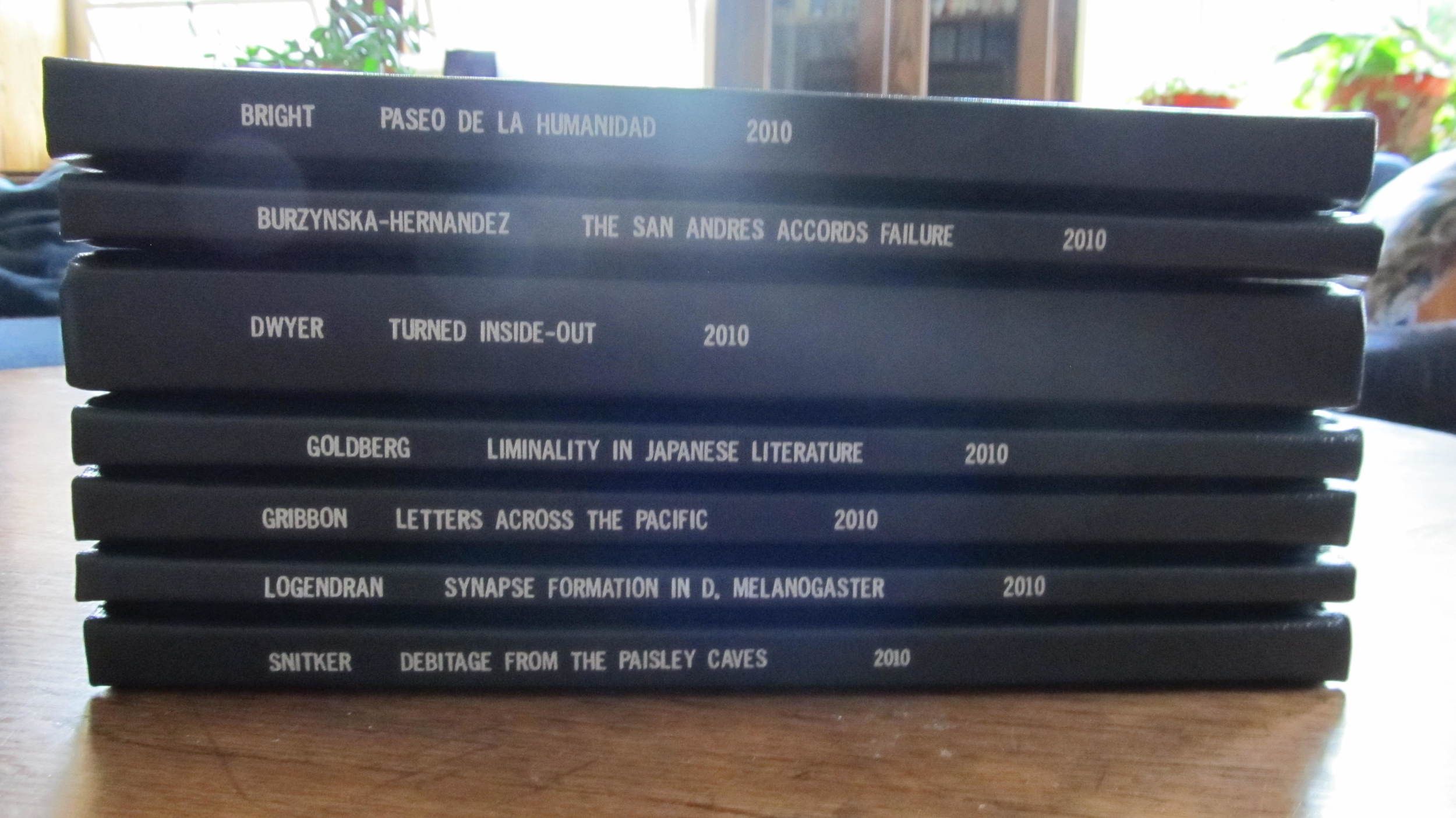

Whatever long and agonizing path you take to get through with your thesis, feel proud of yourself and your accomplishment. Celebrate with friends. Take photos of the final, polished copy. Spend a few days doing nothing, and step back from your hunched position at your computer. You've written a thesis! You're done!

This list of steps is far from complete. A thesis is a long slog of a process. All I can add to this is a reminder to be relentlessly positive, and to be confident in yourself and your abilities. Know that you own this project, and that you can accomplish what you’ve set out to do. Best of luck! And check back for more detailed discussion of various parts of the process in the future.

If you enjoyed this post, you should also check out "Thesis Writing: The Basics," "Thesis: The Defense," and guest post "Making the Most of Your Thesis: From Classroom to the 'Real World,'"

Have you written a thesis? Was the process similar to what I described? What do you see as the most challenging part? What strategies worked best for you? Any comments are most appreciated!