Peer Editing: Guest Advice from an "Editee"

/Note from Katie:

Miles Raymer wrote the first guest post on MyCollegeAdvice: "On Choosing a 'Useless' Major." He and I have been friends since our freshman year at the University of Oregon in 2006. Over the course of our friendship we have also developed a peer editing relationship that finds each one of us occasionally handing over a piece of precious writing for the other to tear to bits. Miles' guest post is no exception to this rule. He suggested that it might be useful to share our tips for peer editing, as well as to let people glimpse the process through our process on that blog post. So, without further introduction, here is the first of a two-part series on peer editing. My take on the process is coming soon. Enjoy!

The Ins and Outs of Peer Editing by Miles Raymer

You should always look this happy while peer editing. Or wandering around in the forests in Northern California, as pictured here.

I think the most important aspect of allowing yourself to be successfully edited by one of your peers is to moderately distance yourself from your opinions. This goes for any piece in which you are taking an argumentative position (pretty much anything you'll write for a humanities course, and perhaps for courses in other fields as well, depending on the assignment). It's easy to forget that taking the time to engage with academics and then construct a personal response to them is a deeply emotional experience, especially when the authors in question possess superior knowledge, background, and rhetorical savvy. The great challenge of being an undergraduate is that you have to throw your hat into the ring with experts, and then have your attempt judged by another expert. And even if you're just writing for your own betterment and not directly engaging in an academic exchange, as I did when constructing my first article for this blog, there is still an element of throwing yourself into the virtual public square for consideration.

Because of this combination of energy exerted and personal risk, I've found that, especially when editorializing, I often exhibit a strong desire to claim exclusive ownership of my personal opinions. It doesn't help that our culture makes it easy for us to do this by perpetuating the nefarious myth that "everyone's entitled to their opinion," when in actuality most opinions can be demonstrably shown to be superior or inferior to others. If you ascribe to such a view, it's unlikely that you'll be able to receive constructive feedback from anyone. Try to remind yourself that, from day one, we're all subject to the influence of biology, culture, and personal experience. Our opinions are nothing more than the sum total of these three components enacted through our bodies at any given moment; future developments may very well cause us to adjust even the strongest convictions, so there's no use in clinging to your point of view simply because it's "uniquely yours." You're just the transmission, not the signal.

During the writing process, you should be totally engrossed and committed to your argument, but once you have a solid draft and you want to show it to someone for improvement, take steps to distance yourself from the piece. This will decrease your likelihood of reacting badly to a harsh critic and will also free up your mind to welcome advice that may very well improve your work. And if your peer editor is a friend, it will also diminish the chances of marring your friendship if the feedback is different than expected.

I'm sure you probably get this sense from reading her blog, but having Katie as a peer editor is fabulous. She's both attentive and encouraging, has a knack for sifting the wheat from the chaff, and, most importantly––she's smarter than I am. If you have a friend who embodies these qualities, look to that person first for your best shot at building a lasting partnership from which both parties can benefit.

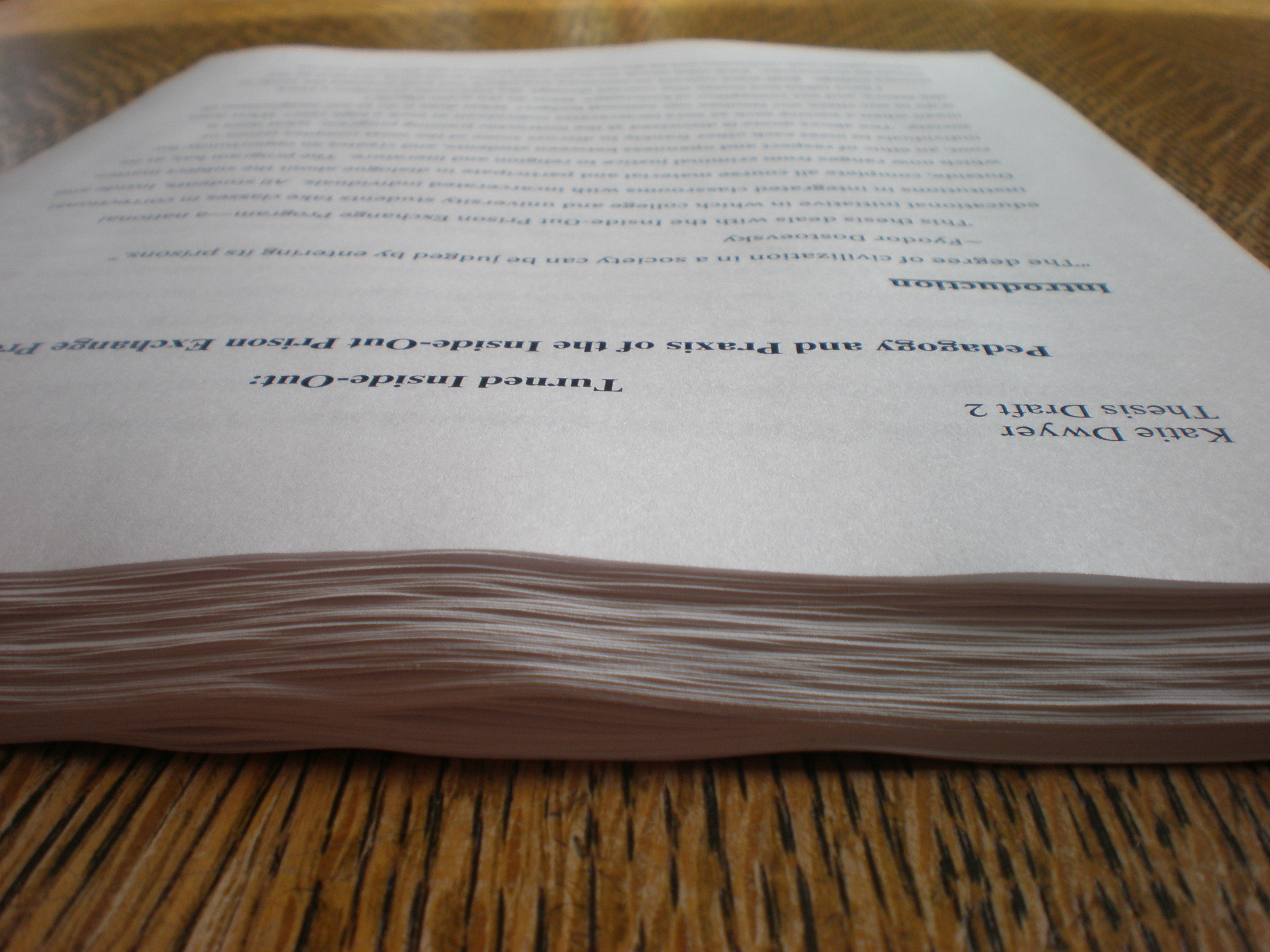

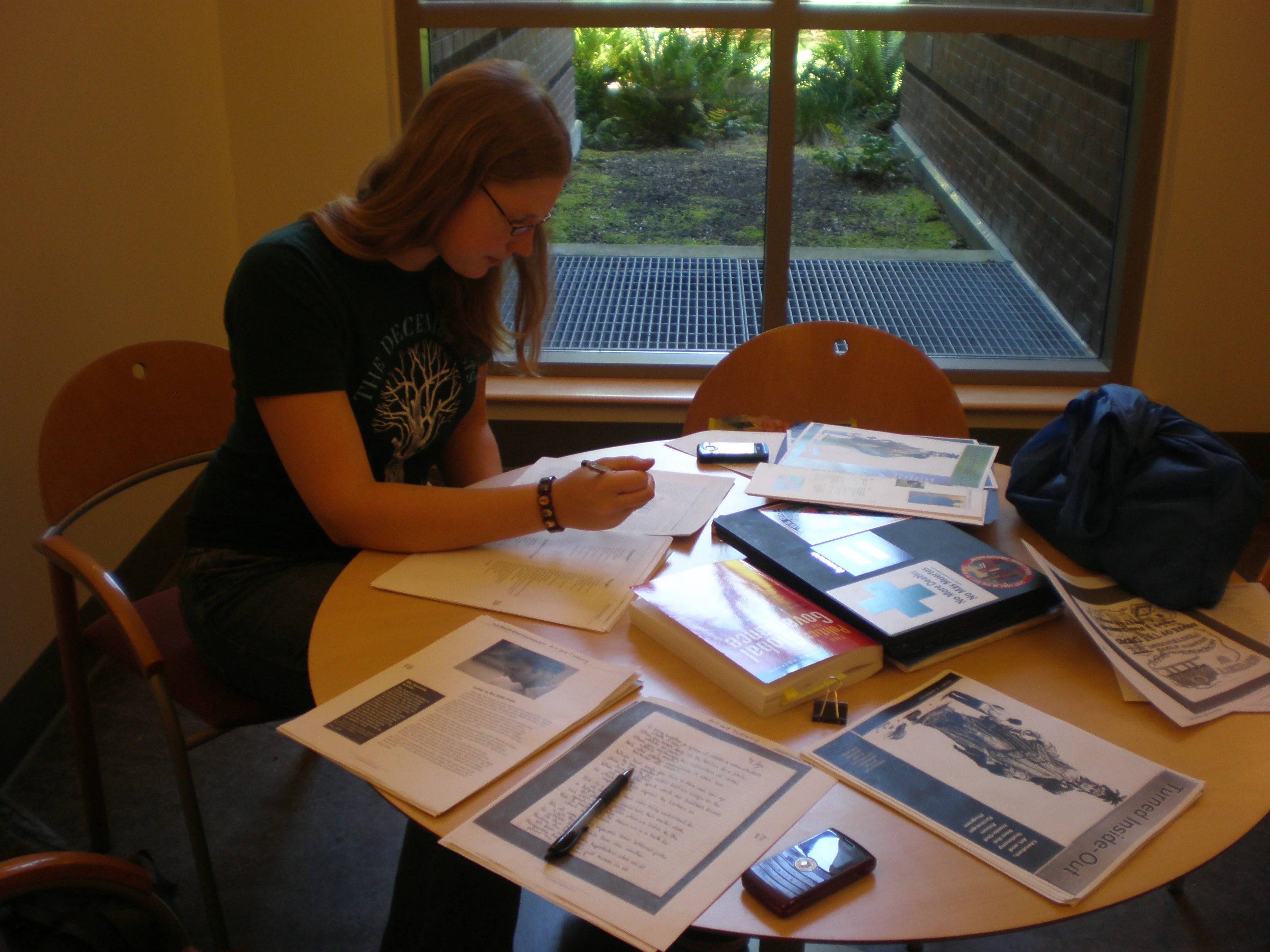

As far as the article in question, you can see that it went through some very serious revisions in just three drafts. (You can read the first draft, the second draft, and the final, published version for comparison) With Katie's helpful guidance, I had to let go of certain parts and expand on others. In some cases I had to be stubborn about preserving a particular phrase or argument, while in others I happily capitulated. The final product was something better than I could have ever written by myself because I allowed another person to point out where I was on to something good and where my thinking was myopic. I've no doubt the piece could have improved further had we taken more time and tapped more minds to help us. But you have to stop somewhere. If you have any questions about particular sections of the drafts or why something was kept or edited out, please make a comment and I'll try to answer as best I can.

Miles' “Dos and Don'ts” of peer editing (for the writer):

DO:

- Choose a peer editor who is both intellectually invested and capable of providing useful feedback relevant to your writing topic. It is also crucial to find someone with knowledge and writing skills that are equal or superior to your own. If you have a great editor who is not knowledgeable about your topic, try to find an additional editor who possesses the expertise you need. There's no limit to the number of different brains you can pick.

- Take risks. Make that wild connection between sources or points of view, even if you're unsure of its legitimacy. Chase that extra tangential thought to its logical (or illogical) conclusion. Unlike with solo writing, peer editing gives you the advantage of having someone to pull you back from the cliff if it's not worth the plunge. Trust your peer editor to help you draw the line between inspired and insupportable argumentation.

- Listen––really listen. When the time comes to sit down and hear your peer editor's comments, don't reduce everything they say to something you think you've already covered in the piece, and don't try to argue that they just "aren't getting it." Remember that even the best writers often overlook major aspects of an issue, especially in the first few drafts. You don't ultimately have to change anything you don't want to, so focus on helping your peer editor feel like his or her comments are appreciated. This is especially important if you want to retain your peer to help you edit future writing projects.

DON'T:

- Don't take things personally. Almost all feedback that's worth hearing will chip away at your self-confidence at least a bit. Take this as an opportunity to learn about yourself and grow, similar to how exercise breaks down our muscles in order to build them back stronger than before.

- Don't stick with a peer editor who isn't right for you. Sometimes you'll pick someone with whom you just don't have editing chemistry. Even your best intellectual companion might not be right for you in this role. If this happens, gracefully admit it and discontinue the process without putting blame on anyone. Hold out for a peer editor who gives the combination of criticism and support that is right for you.

- Don't write too many drafts! Even after completing a masterpiece, artists of any ilk almost always feel that, somehow, an essential element has been left out of the final product. Learn to acknowledge this discomfort and let it pass without allowing it to dominate your writing process. Many smart writers end up not turning in assignments because they're "not good enough." Turning in something substandard is always preferable to holding back entirely because you didn't reach the absolute pinnacle of your ability for any given assignment. Get to a place where your paper is good enough and then move on to something else.

Creating a good relationship with a peer editor can add enormous depth and quality to your work. Cultivate that partnership with a classmate and see where this might take you.

Note: Part Two: Peer Editing for the Editor (written by Yours Truly, Katie Dwyer) can be found here: "Peer Advice for the Editor". Believe me, healthy peer editing takes careful phrasing and a control of tone. And it is a skill totally worth learning. Also, check out Miles' blog, Words and Dirt for some great personal stories and favorite passages from books he's currently reading. For another blog post on how to use your friends for academic purposes, check out "Study Strategies: The Study Buddy."

Have you ever taken on a collaborative writing project? Any additional tips or advice for the peer editing process? Questions? Any horror stories to serve as counter-examples? Please leave your comments, questions, and stories here--Miles and I promise to get back to you.