Peer Editing-- For the Editor

/Last week, Miles Raymer wrote a great guest piece about the value of peer editing, and the difference it can make for both the writing process and the actual formation of ideas. With a good peer editor, you have the chance not only to ensure that you’re not making basic errors, but also that your arguments are solid. You can take risks. You can stretch your opinions. You can create a discussion that starts with your solitary ideas on the page, progresses through the eyes of a peer, and then ends in the hands of your professor. What an incredible boost to your academic opportunities and the ability to interact with your own ideas.

Miles shared that we have become “partners in crime” in the peer editing process. In his piece, he gave some basic and crucial advice for the “editee.” I will here share my advice as an editor. As both of us have been in both roles, hopefully these two pieces will form some kind of coherent whole.

Peer Editing Advice for the Editor

1. Be mindful of the other person’s feelings.

Miles advises editees that they set their egos aside. This is good and critical advice, but as a peer editor you have to always keep in mind that your tone and delivery of editing can significantly impact how your advice is received. This can be as simple as not writing “THIS IS STUPID” in large red letters next to an argument you disagree with. (Let’s assume you wouldn’t be that insensitive, no matter how strongly you might feel about something.) People are sensitive about their writing. Here’s a couple of strategies I have while offering critique:

- Always begin with praise. Tell them what they’ve done well before you point out any errors. In addition to building some comfort, you’re also letting them know that you honestly like their work and want it to be better. That’s a great place to start an editing process.

- Explain your edits. If you have a large suggested change, make sure you explain why, in writing, on the page. Never cross out more than a sentence without saying why. This will also help them with future projects if they have a first example of what didn’t work well in the past.

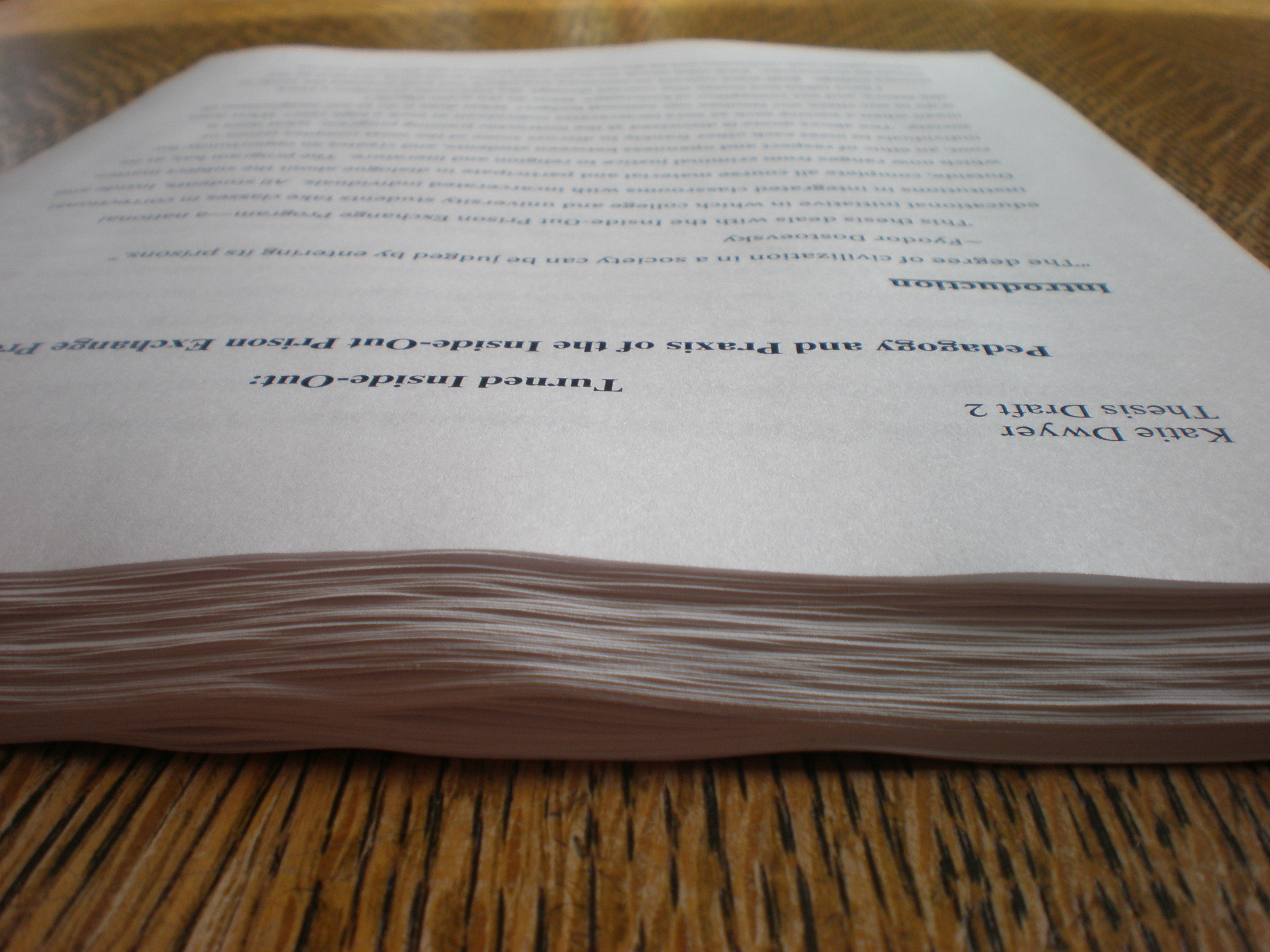

- Benefit of the doubt. If some large error has been made, write “I’m sure you would have caught this on the next edit, but…” I once edited a friend’s thesis draft and she had consistently misspelled the topic. She had just gotten it into her head the wrong way, which I have certainly done in the past as well. Better to bring it up in a kind way than let things slip to spare feelings.

- Intersperse corrections with positive comments. If you’ve just torn apart two paragraphs, but the next one is absolutely spot-on, go ahead and say so. The words “great example” or “really strong” next to a section of writing can soften earlier blows and encourage corrections in that vein.

- Timing and tone. Try to keep the writer in mind as you’re editing. Just imagine how your suggestions will be read, and make sure you’re not being unintentionally hyper critical.

- End with praise. At the end of the process, re-affirm what worked well about the piece. Again, this builds confidence and also brings things back to the whole point—that you want a good piece of writing to become better.

Even if you’ve been asked to give corrections, remember your friend's delicate emotions. Critique in a spirit of encouragement and giving. If you’re not mindful of this, you risk the writer thinking that you’re being hypercritical instead of helpful. Be gentle, particularly with first-time editing.

2. Have a system.

Be consistent with how you write down your changes. I use a combination of colored text, strikethroughs, and the “add a comment” function in Word. You can also use highlighting and Word tools like “track changes.” The key is that you don’t just go through and make changes. You want it to be clear what you think needs work and, where appropriate, what specifically you think could be added to improve the writing.

Editing Miles' guest piece.

(You can see in this screen grab of the piece Miles wrote “On Choosing a ‘Useless’ Major” that I had some significant thoughts and suggested changes. And you can clearly identify what those changes should be.)

3. Ask for a focus.

Is your writer primarily interested in mechanical edits (grammar, phrasing, spelling, etc.) or in style, development of the argument, or the completion of external requirements (such as the assignment/answering the question)? Keep an eye out for all of these elements while editing, but allow your writer to dictate your focus.

4. Pay attention.

This is the final piece of advice, and it’s absolutely critical. Pay attention. Read deeply, track what you’re doing, and be able to comment on the suggestions you make. You have been trusted with someone’s writing. Do them the honor of truly engaging with their argument, getting to the roots of their subject matter, and generally doing all you can to interact with their piece.

To end this post on editing, I want to share a quick story. For many years I’ve taken part in creative writing groups of varying membership and format. I don’t think writing should be a solitary task: at least in my experience, some of the best writing gets done with the company and support of others. I have recently become a member of the Dublin Writers’ Forum, which meets every week for a “read and critique” session. Each member brings twenty copies of a short piece of writing. We take it in turns to pass around the copies, read the piece aloud, receive feedback, and offer a quick “rebuttal” of those comments. Then we collect the copies and move on to the next person. It is fast, intimate, and an incredibly powerful way to improve writing quickly. I absolutely love it, and it has changed the way I write as well as the way I edit.

Find a community to share your writing. Whether it’s a peer in your major or a friend from back home, try to build a relationship with a peer who can offer quality feedback on your writing, and who will entrust you with their work in return. It can make an enormous difference in the quality of work and the experience of academic thought.

Related posts: "Peer Editing: Guest Advice From an 'Editee'", "Thesis Writing: The Basics", and "Study Strategies: The Study Buddy"

Do you have a peer editor? Have you been asked to edit someone else's work? Do you have other suggestions for editors? Positive and/or negative experiences to share? Please leave your comments here.